Brittany Rogers is a poet, visual artist, essayist, high school teacher, and lifelong Detroiter. Audacity is the overarching concept that activates her creative process; as a Black queer femme, Brittany is fascinated by the boldness and risk taking that daily survival necessitates. As such, her explorations of audacity often lead to an interrogation of the connections between the audacity of Black women and pleasure, longing, autonomy, the erotic, adornment, coming of age, and matrilineage.

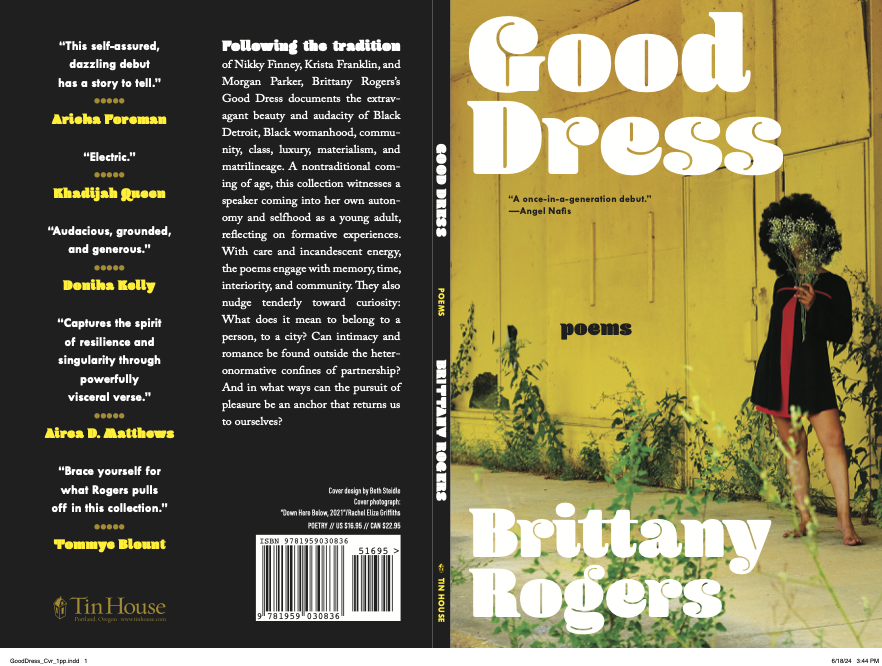

As a whole, Brittany’s creative work pokes at the notions of respectability, ownership, beauty, and obligation, and is constantly looking to subvert the heteronormative and patriarchal expectations that are placed upon Black femmes. She has work published or forthcoming in Prairie Schooner, Apogee, Indiana Review, Four Way Review, Underbelly,Mississippi Review, The Metro Times, “The BreakBeat Poets: Black Girl Magic”, Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora,Lambda Literary, and Oprah Daily.She is Editor-In-Chief of Muzzle Magazine and co-host of VS Podcast. Her debut collection, Good Dress, is forthcoming from Tin House Press this fall.

…

Interview with BRITTANY ROGERS:

What does the word audacity mean to you right now? Has your relationship with that word changed over the past year?

I define it in my critical work as having the nerve to do something. It’s usually one of those things that people say when somebody does something they don’t like, but they kind of respect, like, I can’t believe this person had the nerve to do this thing or that thing.

My mom is always talking about me having the nerve to change my hair, and all sorts of things that are considered bold or tenacious. I think that when I use audacity, I almost always mean it as a compliment. That has shifted for me definitely over the past maybe four or five years.

Because I think before when I heard audacity, it was usually more of a put down and more of a word used to define somebody who was doing something maybe they shouldn’t have been doing. And I think that the more I reflected on the word, the more I wanted to challenge the idea of, okay, but who says they shouldn’t be doing this?

Is there something beautiful about being audacious for you?

I think so, absolutely. I think audacity is what keeps us alive. I think the ability to say, this is not what I am expected to do or supposed to do, this is not the safe choice, and to then make that choice anyway, I think is something very beautiful. And it’s something that when I’m able to lean into it, makes me feel very powerful, very strong.

Where do you derive your strength from in order to be audacious?

My mothers. And when I say mothers, I mean my mom, my granny, my aunts, my cousins. My matrilineage basically. I think that there is literally no way for me to look at them, and to look at my history, and be anything other than a bad bitch. They remind me constantly that I can absolutely juggle anything.

I was raised by a single mother. My family is very much a matriarchy, so my grandmother and all her sisters married, divorced, never married again. I have a couple of uncles, a couple of male cousins, but for the most part, my family is just women. And to watch them survive as girls on the east side of Detroit is proof for me that I can do anything.

What is the cost of not being audacious?

I think black women, especially, who are not audacious, usually end up having to settle for something that they don’t want. I think the gap between where I am and where I want to be takes a lot of audacity, to think that I can close that gap. And I think that there are worlds in which I can say that gap is impossible, so I could not go for it. And that would certainly be the less riskier choice. But I think it would also be the safe choice that doesn’t really serve me. I would have to shrink myself a lot to maintain that. And that’s just not something I’m interested in doing.

I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to be a caretaker. I’m a mom, I have a young son, and then also my dad is old and going through some things, and suddenly I’m the only one who’s taking care of him. He has no other humans in his life. I’m thinking about caretaking in specific relationships, but also in all the ways we are deeply interrelated, and our survival is deeply interrelated. In Pantoum for Postpartum, you write “Mama just means keeping someone else alive.” Is there something more you can say about that concept, and what it means for you in the ways that you are keeping others alive?

First, all solidarity to you as a caretaker. I was one of my grandmother’s caretakers in her last days of life, and it’s a very big honor. And it also was a lot of responsibility. It was a lot of feelings, and I still have a lot of grief around all of that. So all solidarity to you.

I have three kids, and everyone in my house, parents on down, has either autism or ADHD or both. So there’s lots of caretaking required there. And I think, again, growing up in a matriarchy, there are just a lot of ways in which care was a very communal responsibility. And it doesn’t necessarily matter who belongs to who, it matters that that person’s taken care of. So there are plenty of days I spent at my cousins’ house, and plenty of days that they spent in my house, and plenty of days where we all spent at a collective aunt’s house.

And it wasn’t important whose child is this, who does this child belong to. It was just, okay, let’s make sure that everybody is taken care of, whether that is financially, or materially, or emotionally. I think all of those things factor in. All of that upbringing models the way that I view parenting and the way that I view caretaking, as very much an emotional and moral responsibility. And I suppose also an obligation, although obligation has a connotation I’m not crazy about, because I enjoy caring for people.

A feeling that I love, that I don’t talk about often, is that I love feeling babied. I love when somebody is rubbing my hair, and taking care of me, and making sure I’m good. And I like other people to have that feeling. I like to give that feeling to other people. What I probably need to unpack is that at some point caretaking became a lot of my identity, not just with my kids, but I think because I’m a teacher, I am constantly engaged in caretaking, and then family dynamics and politics. I’m the oldest daughter, the oldest granddaughter, the oldest niece. So when it comes to things like that, I’m usually one of the first calls. And, you know, trying to balance caring for other people with making sure I’m caring for myself.

Do you feel like in your creating, you also have a collaborative, mutually caretaking kind of community?

Absolutely. And probably more so because, you know, family dynamics-wise, once it’s looked at as like, okay, this is this person’s role, this is this person’s job, then other people feel like they can step back from the job. But I think creatively, I have a very, very close group of friends. And then I have even a wider community that I think thrives on the idea of a communal experience.

So we’re going to workshops together, we’re creating little residencies together, we co-work together all the time. So when it’s application season, I’m not applying to things by myself. I am on the phone with people, on Zoom or on FaceTime, and we’re like, okay, what question are you on? Okay, I’m on this question. Can you read my answer? Can you look at my sample? This is the order that I’m thinking, but does this order make sense to you? And we’re doing those things as a collective unit. I think in my creative community we don’t believe in the idea of scarcity. We don’t believe in the idea that there’s going to be just one person who makes it. We think we make it as a community, or we don’t make it at all.

Because of that foundation, it makes it really, really easy to share processes with people. I get my best generating done when I’m thinking with others. There is not a draft of my poetry that Ajanaé Dawkins has not seen as long as we’ve been friends, and we’ve been friends for 12-13 years. There is not one draft that I have written that she has not seen, and vice versa. There’s not one draft that my husband hasn’t seen, and vice versa, because we met through poetry. We didn’t meet through traditional channels or whatever. He was my poet friend before we were partnered in any way.

That idea of care–I am just as invested in what happens in their work and in their practice and in their generating as I am in my own work–is really a core foundational center for us.

There was an interview you did with the Hopkins Review in 2023, and you said, “I’m often thinking about the metaphors from the music that I grew up listening to, and I think they taught me to like images that are not obscured, things that are very vivid that you can’t look away from.” I’m curious if you could talk a little bit of about the value of this last part, why does it matter to you to create something that’s unobscured?

I think that for as much as I’m in academia—I’m an educator, I have an MFA, I would love to teach at the collegiate level at some point—I do not necessarily consider myself an academic. I consider myself a scholar, a person who wants to learn forever.

But my audience is not academia. I tell people all the time that my primary audience is black femmes from urban cities. You know, the girls with the waist-length braids and the long-ass nails. Essentially, I write for who I was as a youth. Ntozake Shange once said that she writes for little colored girls who aren’t even in the world yet, with hopes that when they get in the world and see it, they’ll know that they were loved before.

That’s my goal. Because that’s who I’m writing for, and to, I don’t want them to get to my work and feel like it’s inaccessible for what we’re talking about, for the conversation that we’re having. And I think that part is just very, very important to me.

It also is not how I talk. There is certainly a value in that type of poetry. And I read that type of poetry. To be fair, I think I read very, very widely. So I don’t want to say that it doesn’t have value because it certainly does.

I’m usually not the audience for it. And it’s not for my audience.

So that leads me to another question that I have, which is—you talk about how much intimacy and tenderness is important to you in your relationships with people and the world around you. And this is something I think about all the time. I teach, and I’m in academia also, and as an artist and a human in the world who’s trying to keep their integrity with their feelings and spirit, and then being in these institutional spaces, I’m curious, how are you negotiating that, the playing the game versus really being who you want to be in the world?

That is so, so real. I think that right now, in some ways, it’s a little bit easier because I teach K-12 and I just plotted and played the game until I got to a school where I could be myself and then I stayed there. I work at a school that’s really, really big. It’s very hard to micromanage teachers when your school has well over 100 teachers and 2500 students.

And I think I got to a position in my job where, not to toot my own horn, but I’m really good at my job. So they kind of leave me alone. And there are lots of ways in which I think that my admin roll their eyes about me. Like I come in with a new piercing and they’re just like, hmm, okay Ms. Rogers. Or I’m wearing a shirt that says, you know, This justice system is criminal, and they’re like, ok cool, very deadpan. But you know, if the question is whether or not I do my job, I do my job very well. I build excellent relationships and rapport with students, and I think that that’s what they care about the most. So I’ve been able to kind of play the game by really playing to the areas that I’m strong at, and the areas where they care most about, which is pedagogy and relationships. And, luckily for me, I am a great in those areas.

I think that there are ways in which I’m sure that it will get more complicated as I navigate different forms of having a career. I think that is where I have to just really, really lean on my ethics and what I value most. And I try to only align in spaces where I feel like they can accept my values, which is that I care very deeply about community and the rights and care of my community. And if I can’t prioritize that care, then I’m probably not in the right space.

What do you want your book Good Dress to do in the world?

I would love for readers of my book to think more deeply about themselves. I think I’m a very interior writer, and I think I’m a very interior person, for that matter. And I think sometimes that makes people uncomfortable. I talk about feelings very openly. I’ll probably talk about things that in hindsight, after the fact, I’ll be like, Damn, I shouldn’t have said that.

Things that people may not talk about in the first conversation or whatever, I’m like, let’s just launch right into it. I really don’t shy away from confrontation or anything like that. And I think that all of that is true in the collection. And I hope that people are able to sit with that. And I hope that if there are spaces where it makes them uncomfortable, that they’re willing to lean into that discomfort. Because I think there’s something that’s so valuable about knowing yourself and knowing your interior values, or needs, or wants. And I hope that my book pushes people to think about those things for themselves. We all know that all poetry is political, and I think it’s easy if you’re like, okay, this person is writing about her city, or this person’s writing about extravagance or adornment, this is not a book that’s about the political. But I think any time you’re thinking about class or beauty, and who gets to be beautiful, or who gets to be adorned, or who gets to be extravagant, then you’re also thinking about the political. And I hope that people are willing to engage with those deeper conversations.

Who are two artists of any genre that you recommend for people to check out?

I’m deeply in love with the work of Krista Franklin, who is a writer and visual artist who lives in Chicago. I can’t remember if Krista is from Chicago or not, but her work is beautiful and has done so much to shift the way that I think and the way that I approach the page.

I am really fucking with Monaleo right now. She’s a rapper from the South who I’m really, really enamored with. So Krista Franklin and Monaleo.

Experience more of Brittany’s work here.